![Voyager Spacecraft [Image: Corbis via Getty Images]](/images/media/Voyager-Spacecraft.jpg)

In the mid-1960s, NASA was abuzz. Only a few years earlier, US president John F Kennedy had challenged the agency to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. A large swathe of its more than 400,000 employees was working on fulfilling the president’s dream.

But when California Institute of Technology graduate student Gary Flandro arrived at the agency’s doors, no one really knew what to do with him. He was stuck in a corner office and given the task of finding the most efficient way to send spacecraft to the outer planets.

During his research he realised that, in the 1970s, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune would line up in a way that only happens once every 176 years. Such alignment meant a spacecraft could use the gravity of one planet to “sling-shot” to the next, therefore saving fuel and time. Flandro realised this opened the door to visiting all four planets in a single mission, something never done before.

Thanks to his discovery, NASA eventually launched the Voyager missions in 1977. Voyager 2 took advantage of this rare alignment and visited all four planets, sending back amazing data and pictures. This type of breakthrough doesn’t happen without a culture of innovation. One that encourages curiosity, fosters psychological safety, embraces and learns from failure.

“People get scared about innovation,” says David Keene, co-founder and CEO of Coventry-based tech firm Aurrigo. “They think they have to create something that the world has never seen before and that’s quite daunting. Every idea most people have, somebody has had that idea before.”

Innovation is embedded at the heart of Aurrigo, which is developing self-driving vehicles for the aviation industry. For Keene, a simple way to make innovation more of a focus is to step back from the business and pretend you know nothing about it.

Then you ask the following questions: “What do you see? What are the company’s capabilities? Is there another sector that you could transfer the company’s skills to? Are there people in the organisation who could be used in other ways?”

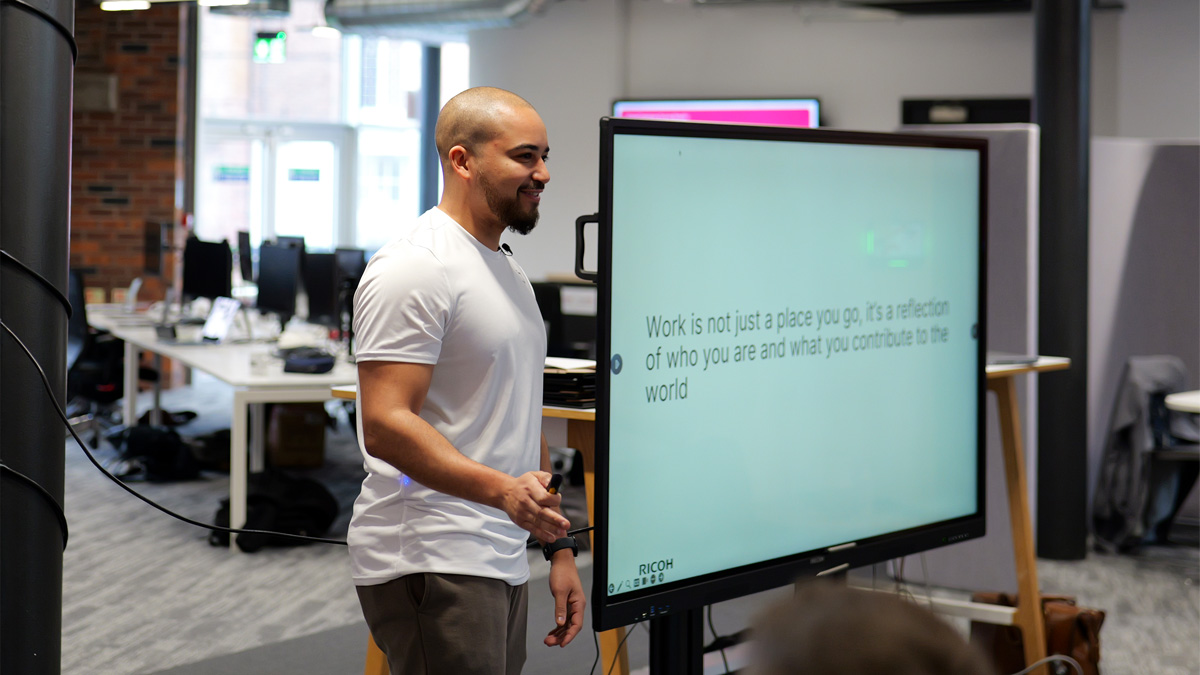

One example comes from Ricoh. “I’d been doing a lot of media and I needed headshots for a media pack,” says Nathan Thomas, Ricoh Europe’s director of innovation. “Our senior technical architect, whose hobby is photography, came in and did them. I’m a huge believer in skills, not roles.”

Ricoh’s environment is deliberately equipped for this thinking. Its office in Birmingham, where Thomas works, is designed to be a “centre of excellence for innovation”. It’s a listed building on one of the city’s canals with exposed brickwork, open collaboration spaces and workstations with beautiful large monitors.

“Everyone’s got a MacBook, which sounds crazy,” says Thomas. “But if you come to work and think, ‘I hate this,’ it doesn’t inspire you to do your job.”

A focus on the shiny new product or service-side of innovation loses the smaller ancillary details that Thomas and Ricoh address in their offices. This is one of the fundamentals of an innovative culture: it starts with your attitude and mindset as a leader.

Having a lightbulb moment around mindset changed the course of Aurrigo’s journey – specifically, the introduction of mobile phone cameras. Although the concept is ubiquitous today, Keene recalls thinking it was the most ridiculous thing he’d seen.

“Very shortly afterwards, I realised what a hell of a mistake I’d made,” he says. “That is one of the turning points in my life. From then on, I agreed that if someone is doing something, or trying something, to never put it down. Go and have a look at it and work out why they’ve done that and how we could exploit it.”

Richard North, president at innovative toy manufacturer Wow! Stuff, gives his teams permission to innovate by even the smallest of actions. “I will say something really stupid, sometimes deliberately so,” he says.

“You might get laughs and I don’t mind. What we’ve recognised is that you get this iterative process where a person will add something to the idea, then another person adds to it. Stupid ideas can morph into something brilliant through teamwork.”

This is an example of psychological safety, the idea pioneered by Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson in her book The Fearless Organization. She encourages leaders to set the stage by establishing clear expectations about failure, uncertainty and interdependencies. Be clear about what’s at stake, why your work matters, who benefits and why. The aim is to create shared expectations and meaning.

At travel company On the Beach, the business’s innovative culture is embedded in the belief that if something is easy, everyone would be doing it. Zoe Harris, chief marketing officer, believes that to differentiate, businesses must keep trying and pushing what’s possible. One of her best examples of psychological safety comes from her time at the publisher Reach.

Along with Alison Phillips, Harris led the launch of a newspaper called The New Day. It was set up to introduce a new revenue stream by attracting readers who were churning out of traditional papers. It had its own unique production process: it borrowed content from across the group, targeting a specific demographic driven by consumer insight and data.

It closed after two months.

Harris was mortified. “The company spent lots of money,” she recalls. “I was personally embarrassed and thought I had ruined my reputation. However, the support of the CEO Simon Fox and the CFO Vijay Vaghela was just phenomenal. At the end, there were learnings that could be taken back into the wider group.”

Fox and Vaghela spoke with staff members, alongside Harris and Phillips, when they closed the operation. Instead of being shown the door, the pair were given promotions. The internal and external messaging after the closure was around the need to try new things, be disruptive and innovate.

“Not everything you do is going to hit the mark the first time and that’s okay,” says Andrea Morgan-Vandome, chief innovation officer at supply chain software provider Blue Yonder. “You’ve got to say, ‘That’s fine, I’ll learn from it,’ and drive that culture, not only for yourself, but others. If you don’t do that, people get stuck and become risk averse.”

Morgan-Vandome’s other piece of advice for maintaining a culture of innovation is having a laser focus. “What do your customers want? What does the market want?” she asks. “There’s no point changing for the sake of changing. You’ve got to change to drive value.”

Often, working with customers directly can aid innovation. Keene’s team at Aurrigo developed a four-seater autonomous pod that is used by clients such as airports and sporting venues. One customer requested that instead of people, the pod carry a battery pack – turning it into a mobile charging station. This led to the company launching a new range. It now works with customers to develop products of most use to them.

“If you look at the advancements on the vehicles we’ve got, we didn’t think of those advancements because we’re not in the airport game and our customers have never seen the tech before,” he says. “Together, we developed the products even though neither of us knew the ideal solution.”

Morgan-Vandome says that Blue Yonder’s best practices include working with its clients to ensure adoption is baked into the process of innovation. The company is in the business of supply chain transformation, so allaying concerns and fears around AI adoption is key. This insight came from a recent survey of 700 senior supply chain leaders across Europe and North America.

“Some 83 per cent of respondents were embracing AI,” she says. “But when you dug into it more, newer technology like generative AI was less than 40 per cent. When I talk to a lot of these people, it’s questions like, ‘How do I get started?’ This is where you almost have to break it down and iterate on getting it there.”

So how do you implement generative AI into a warehouse? Morgan-Vandome and her team ask their customers what challenges they face and work with them to discover the cause. They then build and implement AI agents to help with day-to-day running and improve efficiencies.

“If you’d gone to the customer a couple of years ago, built a solution and given it to them, I think adoption would have been a lot lower,” says Morgan-Vandome. “So instead, we asked, ‘What’s the challenge? How can we add value?’ And then everyone wanted it and wanted to give it a go. I think you’ve got to continuously look at what needs to change and it’s not always everything.”

On the Beach leans on customer insight for its innovation. It noticed that customers were holding off booking holidays in January, as they believed prices would go down – despite On the Beach communicating this was the best time to book. Harris and her team softly rolled out a price-drop protection that offered customers credit for the difference in price should it reduce between the time of booking and 60 days before the trip.

“We worked out how we can have a propositional message around proving that January is cheap,” says Harris. It started with its marketing messaging on the website, email and social media. A process was built: if a customer found a holiday cheaper, they had to go online, fill in a form and it was manually done by the finance team.

“When we saw that get traction, we productised it,” she continues. “Now you can go into the app, press one button and it will tell you if your holidays got cheaper and produce a credit note.”

The team identified this opportunity through insight, proved the concept and worked quickly across multiple teams to roll out the solution. On average, customers received around £20, but the company’s biggest refund to date is £1,596.

Thomas and his team at Ricoh adopt dual-track agile methodology. It’s a way of working in product development that helps teams be both innovative and efficient, split into discovery and delivery.

“When there’s something new that we want to try and achieve, we bring some of the core team and people who we think will have a valuable input,” he says. “We discuss and collaborate on it. We’ll then break out.

“So for example, one of our designers will go away and have a think about it for a week. We’ll then come back and discuss the findings. That enables us to move way faster than if we tried to sit down and get a project-functional specification, as was done in the past.”

The company even has a budget to cost in time for designers to spend on innovation.

“If you just do these things naturally,” Thomas continues, “then people will not be scared of producing something that isn’t production-ready or isn’t going to go anywhere. This also means we shouldn’t fail at the stuff that we know but we can fail before we know what we know.”

Thomas sees that to those not involved in these collaboration meetings, they may seem like arguing. However, all employees are primed with a very simple message: you are not your ideas.

“If someone hates your idea, it’s not you that they hate, they just don’t like the idea,” he says. While this may seem like a simplistic message, it goes back to the theme of building an environment that enables people to think and share.

“It was even hard for me years ago,” he says. “Putting the right mix of people in is vital. I’m directly confrontational when I want to challenge people so that they do better or think more. Then there are a few other people we put in with completely different personalities.

“Our head of design, Dean, is the most chilled person you will ever meet. So he’ll be the level head. Then there are other personalities, like one of our UX experts, Ruth. She’s sceptical about absolutely everything and wants to know more detail.

“When you put us together in a group, we end up doing something really great, because we’re all playing different roles that the team needs. If there were 10 of me in a discussion, it would be awful. We’d never get anywhere and nothing would ever really get done.”

Something else that is key to innovation is diversity – of background and thinking. Thomas speaks regularly about what diversity really means in business and has noticed a part of the conversation that often gets missed.

“People would go, ‘We need to be diverse: we need more women or more Asian people,’” he says. “But if there was a woman, an Asian person and a white person next to me, and we’re all living in the same area, with the same background, the same thoughts and feelings, is that diversity? I don’t think it is because we’re all similar people; we just look different. I’ve always been a huge believer in true diversity: diversity of thought, backgrounds and feelings.”

The race to develop AI has shone a spotlight on the importance of having diverse teams working on projects. Siri and Alexa were much maligned for their inability to understand accents when they were launched in 2011 and 2014, respectively. This was pinned on the lack of diversity in the tech’s training phase.

Diversity extends outside gender and race. Age, socio-economic background, disability and accessibility need to be considered when building teams or developing products. Having a broad range of lived experiences doesn’t just mean you get different ideas and viewpoints; it also makes good business sense.

In 2024, Microsoft reported record revenues of $245bn. Chief diversity officer Lindsay-Rae McIntyre stated: “Our innovation has come from our commitment to diversity and inclusion and our future innovation depends on it.”

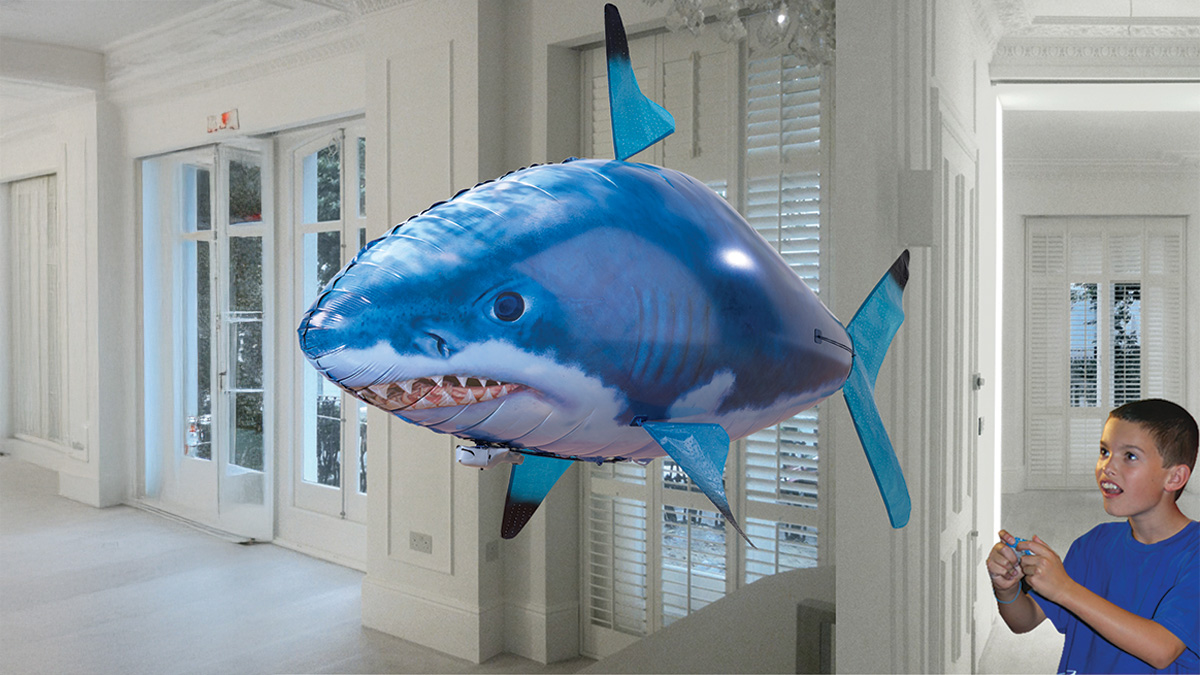

Another element to being innovative is shared by North: it’s great being first to market, but you need to be first in the minds of the consumer. For example, in 2012, Wow! Stuff launched a product in Toys R Us in America called Airswimmers, which was a remote-controlled four-by-three-foot helium balloon in the shape of a shark. It was a huge success.

However, when they tried to roll out the product in Europe the following year, retailers refused to take it: instead, they wanted “the original” – a copy of the product made by one of Wow! Stuff’s competitors.

“In Europe, Sky Shark was the dominant brand,” remembers North. “We’d been copied with an inferior product, but it was first in the minds of the retailers and the consumers.”

The company eventually won a seven-year legal battle that went to the Royal Courts of Justice, which stood by Wow! Stuff’s product patent, but the damage was done and the lesson learnt.

“Coca-Cola – the world’s first cola,” he continues. “Heinz – the world’s first range of condiments… the list goes on. You could be first to market with something totally unique. However, if somebody outspends you on marketing and gets first into the minds of the consumers, they will have the appearance that they’re the first.”

Arguably, the most important tip from the experts about the key to an innovative culture? You have to be excited about what you do. “You’ve got to draw inspiration from it,” says Morgan-Vandome, “because you can’t innovate in something you don’t love or believe in.”

“One thing you’ve got to have for innovation is enthusiastic people,” says Keene. “You can’t have people who just want to turn up at 8.30am and go home at 5pm. Not that we whip everybody to work longer hours, but you’ve really got to enjoy what you’re doing.”

As the psychologist Carl Jung said: “The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect, but by the play instinct arising from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with the object it loves.”

Related and recommended

A closer look at the Northern companies turning artificial intelligence into measurable business results

Leaders must realise the tech revolution can achieve its full potential only when human values remain central to change

Many argue the five-day week is no longer fit for purpose, but can a four-day week really work for businesses?

From Rolls-Royce to Marks & Spencer, these CEOs show how decisive leadership can transform Britain’s biggest companies