Entrepreneurs are used to doing things by themselves. When you start a business, it is likely to be just you, a co-founder or two, and big ambitions. As you scale, more people will join. You’ll hire marketers and designers, tech and HR people and someone to sort out the finances. But at some point, you’ll also reach the point where your business needs to bring in some independent oversight.

However, knowing when and how to do that – especially for those who haven’t brought in outside help before – can be difficult. There’s also no legal requirement to do this, beyond naming a director when you set up a business at Companies House, so the timing is all in your hands.

“There are no hard and fast rules,” says Roger Barker, director of policy and corporate governance at the Institute of Directors (IoD). “As you get bigger, there is no regulation that says this size of company must have this number of people or these types of people on the board.”

Nevertheless, most companies will add independent directors to their board over time. This might be because they need finance – many investors will insist on independent oversight – or because they’re looking for improved governance or an outside perspective.

Typically, companies will first add a non-executive director who is not part of the exec team, though this person may well be connected to the business in some way, say a family member or shareholder. Later on, businesses will typically appoint a chairman who is totally independent, as well as non-executive directors.

“It’s a gradual process,” says Barker. “And it will depend on things like the extent to which it wants to raise external finance. But when you’re looking at the maturity of a business, the general trend is to go from a board composed of insiders to a board with a balance of insiders and outside directors.”

BGF is a private equity investor focused on the scale-up market. Founded in 2011, it has invested more than £4bn across 600 businesses and helped to introduce more than 500 non-execs to them.

Sophie Birch is a talent network manager, leading a team focused on introducing management teams to experienced directors who can join their board. BGF will typically not invest unless a company has at least an independent chairman and tends to take a seat on the board itself.

BGF, says Birch, is “absolutely convinced” that having a non-exec on the board is key to business success. She describes the work her team does as “matchmaking”, working with founders and chief executives to help them understand and develop their thinking around board composition. “We are building a high-quality network of external talent and then matchmaking it with our portfolio,” she says.

Why hire non-executive directors?

The key motivation to bring an independent director on board is, as Birch puts it, to act as a “sounding board” for the founder and senior team. They also need to be available – someone who turns up once a month for the meeting, having read the board pack on the way, is not going to add any value.

Sector-specific knowledge is not as important as bringing skills and experience that the senior leadership may not have. For example, the non-exec may have scaled a business before, have experience of working in an investor-backed business or bring different leadership or technical skills.

Variation of thought is also key. “A diverse board where you can challenge thinking and offer new perspectives is absolutely what we strive for,” says Birch.

As the IoD’s Barker highlights, there are also practical skills those hiring a non-exec director should be on the lookout for. If they are to be the chair, they need to have the skills to run the board. That means understanding the process side of board meetings: how many there should be, what is discussed at them, who is invited, but also the dynamics within a meeting, such as how contributions are listed and made, the appropriate way to challenge and what to do if the board can’t agree.

“There’s a big skillset around being a director,” says Barker. The IoD has a competency framework with three components: knowledge, skills and mindset. Knowledge is to do with governance, strategy, leadership, finance and, increasingly, technology.

For skills, it is being able to absorb information, being willing and able to challenge in a constructive way and seeing the wood from the trees. Mindset encompasses areas ethics, curiosity and an eagerness to learn. Culture fit and chemistry are also extremely important.

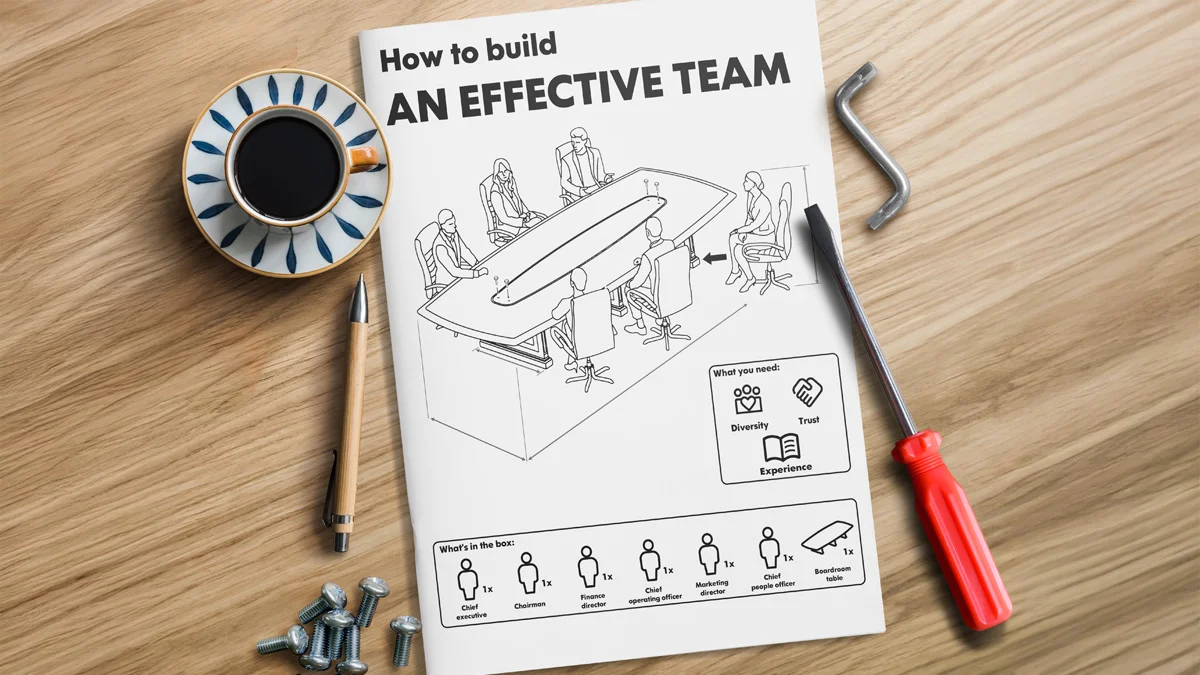

How to structure a board

There are no rules around who should be on a board or how big it should be. In its leanest form, a board will typically consist of a CEO, a CFO (or finance director) and an independent non-exec.

Then, depending on the focus of the business, it might also have a chief technology officer, a chief people officer or a chief operating officer. Birch says she is in favour of “lean boards”, warning of the challenges of having one that is too big.

“Where it can become inefficient is when you have too many people around the board table and not enough time for people to input and share their views,” she says.

Flame PR has just brought its first independent director on board. The PR agency was founded 20 years ago and until recently only had the founder, Kully Dhadda, and her husband as directors.

However, with ambitious growth plans, Dhadda wanted to bring in outside expertise for the first time. She hired her first MD in Alex Brooks, who also joined the board, and at the same time brought in a chairman and promoted her head of business development to the board as well.

Brooks thinks five is a good number for the business to ensure it has the breadth of opinions, skills and experience it needs without getting too big.

“Five, for the size of the business, feels good,” he says. “We’ve got big growth plans for next year and beyond – we want to double the size of the business. Does that mean we double the size of the board? I don’t think so.

“Obviously as you hire more senior people you need to look at the role they play within the company. But we’re at a point now where we have a good balance of people, backgrounds and experience. [When you add more people] they will have their own agendas and opinion, and that’s going to make it harder to balance.”

What a successful and productive board looks like

Ultimately, the point of formalising a board structure is to bring more success to an organisation. “You don’t want to have good governance, but a business which fails. It’s about the long-term success of the organisation,” says Barker.

That means striking the right balance between allowing an entrepreneur or founder to take the business forward, while ensuring that growth is sustainable, that views are challenged and that the company is run responsibly.

For that to happen, says Birch, there needs to be a clear growth strategy so that everyone understands how targets will be reached. “When the board is misaligned and people are looking for different things, that’s a complete red flag,” she says.

Board meetings themselves need to be structured. Flame PR plans its meetings ahead of time and creates a board pack that everyone needs to read, covering areas including finance, people and operations. It also brings what Brooks refers to as a “big-ticket item” to each meeting.

“If you’ve got five people just having coffee and biscuits and talking for four hours every month and nothing’s getting done from it, then what’s the point?” he asks. “By having a big-ticket item, we have something really to sink our teeth into and then go away and do something about. Because you could just endlessly talk about business growth. We know we want to grow the business; the question is how are we going to do it?”

Kim Antoniou is a serial entrepreneur. Her current business, Auris Tech, has five people on its board: Antoniou, her co-inventor Bill Bungay, the chairman Graham Corfield, the company’s chief privacy and data protection officer and the CFO. It also has two board advisers from two funds that have invested in the business.

Her meetings are highly structured, starting with any follow-up from the previous meeting and then a business overview, a sales overview, a technology overview and a finance overview. She’ll also put in the board pack anything else she wants to discuss at the meeting. She warns about meetings that take too long, either because there is too much on the agenda or because attendees can’t agree on the next steps.

“Any meeting that goes on beyond two hours becomes useless,” she says. “If you’ve got a bigger business and board, you might need longer meetings, but they’re just not that productive after a certain amount of time. You need to keep them sharp.”

What to avoid when formalising an independent board

For Barker, by far the biggest pitfall is a tendency for founders to prioritise people who look impressive rather than those most suited to the job.

“There has been a tendency to bring people onto the board that look good from the outside and will be seen as highly respectable, to bring some kudos,” he says. “But you need to ask, can these people meaningfully contribute as a director? Do they understand our business? Have they got the relevant skills and experience to really assist and support us?”

He points to the example of Theranos. It was touted as a breakthrough healthtech company, but it soon became clear that claims about what its technology could do were unfounded. It had Henry Kissinger on the board but later collapsed.

Mismatching is also a common issue. Someone who has worked at a FTSE 100 company might look impressive but is unlikely to have the experience, knowledge and understanding of how to help a company that is in scale-up mode.

Birch highlights that founders can also fall into the trap of recruiting someone too similar to themselves. “That’s something that should be talked about openly and early: what’s the current skillset and experience of the board and where do we need to plug the gaps?”

For Antoniou, the best way to get this right, particularly the first time, is to talk to others who have done it. “Don’t jump into it because you think it’s the right thing to do. I think in the past I should have had more conversations, talked to my network and got some recommendations,” she says.

Nevertheless, Dhadda would recommend bringing in that crucial outside viewpoint. “I haven’t been forced into a board, but I would really encourage any business not needing to, to do it, because it’s such a great foundation to scale a business. Having just done it for the first time, it’s been a wonderful thing to do.”

Related and recommended

The hotel executive believes the hospitality industry needs to be proactive in hiring to reflect society

The legendary ad exec believes leaders should collaborate with the technology, rather than use it as a tool

Entering new markets drives growth but can trip up the unwary. Here’s everything you need to know before you start

Richard Harpin, the founder of HomeServe and Growth Partner and owner of Business Leader, answers your burning business questions