“Learning and innovation go hand in hand. The arrogance of success is to think that what you did yesterday will be sufficient for tomorrow.” - William Pollard

It’s not easy being a business leader. No matter the size of your business, disruption is the goal but it's around every corner. What separates Blockbuster from Netflix, or Apple from Nokia? We’ve analysed five notable businesses that have failed to hold onto their disruptive heights and rooted through the ashes for learnings.

1. Blockbuster

Many a business study has been done on the rise and fall of this icon, but it is the picture-perfect example of a company not adapting to the time. The company was founded in 1985 as a standalone small video rental business but grew to become one of the most recognisable brands on the planet. At its height, Blockbuster employed over 84,000 people worldwide and operated over 9,000 stores. How could things go so wrong?

Analysts have attributed the company’s decline to leadership failures, financial mismanagement, internal dysfunction, and intensifying competition. Business and consumer expert Kate Hardcastle MBE says Blockbuster is a quintessential cautionary tale of disruption gone unchecked. “It failed to pivot when streaming technology changed how consumers accessed media,” says Kate. “It’s a stark lesson that customer convenience often trumps brand loyalty, and those who ignore consumer trends do so at their peril.”

In 2000 and during the peak of the dot-com bubble, Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings offered to sell a young struggling upstart called Netflix to the then-video rental giant for $50m (£40.7m), the same upstart that has a 2023 market cap of over $190bn (£154.6bn). Blockbuster instead chose to partner with Enron on a 20-year deal to create a video-on-demand service. Enron pulled the plug on the deal a few months later over worries that Blockbuster couldn’t provide enough content for the service. Enron would declare bankruptcy less than a year later.

Blockbuster declared bankruptcy in 2010 and etched its place in history as a classic business case study. “Confirmation bias is a common mistake when companies fail,” says Maria Santacaterina, author of Adaptive Resilience: How to Thrive in a Digital Era. “They deny new innovation pathways as executives narrowly focus on ‘data’ but in a fast-changing market, a rear-view mirror often clouds judgment. A flawed business model not keeping up with the pace of change combined with rising debt seals an earlier demise. Fundamentally, the lack of product diversification and financial resilience in this instance, meant Blockbuster could not sustain falling revenues and the dramatic loss of market share.”

2. Nokia

Imagine commanding a 49% share of a global market, only for that to drop to 3% six years later. The Finnish company’s impact on the rise of the mobile phone is undeniable, launching the first internet-enabled phone in the mid-90s and pioneering the touch-screen mobile phone by the start of the millennium. The company’s market cap reached over $250bn (£203.3bn) in 2000 but is now worth around $18.5bn (£15bn). How did it all go so wrong?

The world of mobile phones changed dramatically on January 9th 2007, when Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone. Around that time, Nokia was producing over 50 models. One of them was the Nokia 1100, which still holds the title of the best-selling phone of all time to this day, shifting 255 million units since its release in 2003. However, Apple’s bet on touchscreen phones being what the consumer of the future would want paid off in a big way.

This lack of agility and innovation had a lot to do with their downfall says Sam Page, CEO of digital agency 7DOTS: “They were slow to adapt to the smartphone revolution and underestimated the impact of this technology. If they had truly understood the shift in customer behaviour and truly listened, they would have produced the smartphone and or pivoted the business sooner.”

“Nokia phones were so iconic,” says leadership expert Ellie McKay, “but as other innovative brands entered the market they simply couldn’t compete. It only took a few years for perceptions to shift, they looked outdated very quickly. Mobile phones soon became a status symbol that people aspire to buy the best of, and Nokia no longer fitted that mould.”

The other key factor in Nokia’s downfall was its marketing, and a classic example of this comes from the iPhone 2G. Apple made 15 major technical improvements to the model compared with the original iPhone, and they celebrated each of those as radical and important. Nokia's flagship N95, which was available well before the release of the iPhone 2G, had 14 of those 15 technical abilities as standard features and had numerous features and abilities that even the iPhone 4 did not support. “But somehow with Apple, the facts no longer matter,” says best-selling author and former Nokia employee, Tomi T Ahonen. “The iPhone was the ultimate best phone ever - according to Steve Jobs - because he said so, and that started to become the storyline.”

3. Polaroid

One of the world’s iconic brands is making a comeback. In a world of augmented reality and artificial intelligence, Gen Z developed a point-and-shoot fascination. Best known for its instant film and cameras, and once dubbed “the Apple of its time”, Polaroid is one of the US’s early tech success stories. The company reached dizzying heights of over 21,000 employees and an annual revenue of $3bn (£2.4bn). However, Polaroid’s downfall is another frequently dissected business study, packed with lessons for any leader.

Edwin Land founded the company in 1937, after boasting numerous inventions such as inexpensive filters for polarising light and a practical system of in-camera instant photography. During a holiday with his family, he took a picture of his three-year-old daughter, who promptly asked why she could not see the picture her father just took of her – and the rest is history. Fast forward to 1972 and Polaroid had become a global phenomenon after it released the SX-70, the world's first instant SLR camera that developed the picture as you watched.

Polaroid followed this up with the 1977 announcement of a new Instant Home Movie camera, Polavision, which ushered in the era of the home video. The company was achieving global sales of around $1.4bn by 1979, but Land’s refusal to diversify the company, not entertain a sale or borrow money on a long-term basis started to catch up with them. Polavision wasn’t received well in stores and forced the company to write off $89m (£71.4m), which led to Land’s resignation after more than four decades at the helm.

The attitude toward Polavision was a microcosm of the company’s defensive mindset, according to Graham Winter, co-author of the Toolkit for Turbulence: “Wired to prioritise security, Polaroid overreacted to Polavision's failure and hesitated to introduce new products, hindering market agility. Polaroid thrived on instant film profits but lacked the hunger to foster a culture that challenged and shaped new paradigms in products and business model.”

The company tried to diversify in a declining market, but it struggled over the next two decades, before eventually filing for bankruptcy in October 2001. “Polaroid went from innovation to retro,” says Ellie McKay. “It is well-documented that Polaroid chiefs were risk-adverse and did not want to innovate which was the root cause of the brand’s decline. A lack of strong leadership over the course of a few decades saw Polaroid fail to listen to its own research and development. They didn’t diversify into other products, keeping everything centred on the Polaroid camera.”

Ownership of the Polaroid brand bounced around until eventually being acquired by Polish billionaire Wiaczeslaw Smolokowski in 2017, who has worked to make the most of the nostalgia factor. But there may be a lesson in the brand’s mini-revival: embrace your USP. “We’re surrounded by the digital world, by AI, and the ultra-filtered,” said Patricia Varella, Polaroid’s creative director. “We’re arriving at a moment where it makes sense for us to play in this real-life territory and talk about imperfections. Our product actually embraces that. It’s real.”

4. Toys R Us

“I don't want to grow up, I'm a Toys R Us kid.” The famous jingle from the 1980s, co-created by best-selling author James Patterson, remains one of the most iconic and lasting jingles in retail history. Charles Lazarus set up the company in 1957. By shrewdly negotiating contracts, the company was able to sell toys at prices considerably lower than its competitors. The company listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1978, controlling 5% of the entire US toy market. Five years later, the retailer doubled its number of stores and its market share jumped to 12.5%. At its peak, the company had around 1,600 stores and up to 100,000 employees across the world.

A pivotal moment for Toys R Us came in 2000 when it inked a 10-year partnership with Amazon to be its exclusive seller of toys. “They didn’t believe in the internet,” says serial Entrepreneur Gary Vaynerchuk. “It got people used to buying toys online - through Amazon, not Toys R Us. When you don’t innovate, you die.” The success of the partnership led Amazon to expand its toy category, but despite an ensuing lawsuit being successful, the $51m (£40.8m) payout didn’t make up for the years Toys R Us ignored building its own e-commerce strategy and online presence.

The company opened its flagship store New York Times Square in 2001, dubbed the world’s greatest toy store. Thousands of customers visited the location for the ultimate toy retail experience, which featured arcades, a life-size Barbie dreamhouse, an indoor Ferris wheel and much more. However, to cut costs, Toys R Us management closed the store in 2015. Their lack of appreciation for experience was evident in many stores across the globe. “When my son was young, I took him there a few times,” says Olga Valadon, the founder of leadership, strategy, and culture consultancy Change Aligned, “but I never saw the same excitement on his face that I did when we visited the Lego store. How are they different? Toys R Us was just a massive place where one could buy toys. Competitors, such as Lego, understood that customer experiences were the key to selling.”

“The dramatic shift to electronics and video games in the first two decades of the 2000s was not addressed,” says global strategic leader, Maria Santacaterina. “Parents were buying less physical toys and shifting to digital entertainment and games for their children and this was largely ignored. A lack of vision and strategic direction failing to read profound changes in consumer behaviours led by competitors left the company vulnerable to declining revenues and market volatility.”

Toys R Us filed for bankruptcy in 2018, closing stores across the globe, including their UK operations which were snapped up and rebranded by Smyths. The company has since tried to rise from the ashes once again, opening more than 20 stores State-side and launching an online presence in the UK, a far cry from the “category killer” the world had once known. “Just like a performer on stage, they failed to read the room, or in this case the market,” says author and renowned retail thought leader Andrew Busby. “Change is constant, but they stuck to their formula and refused to recognise the changing world around them.”

5. Myspace

“Myspace was significant in creating the culture we see today,” says Ellie McKay. Founded in 2003, it was the original social network and, within three years, the disruptive upstart had surpassed Google and Yahoo as the most visited site in the US. At its peak, the company had over 300 million registered users and was worth $12bn (£9.6bn). This was an astronomical amount in 2007 for a brand-new market but is a drop in the ocean compared to today’s figures: Facebook has over three billion users and its parent company has a market cap of $864.2bn (£693.4bn).

In 2005, the company’s funding boost came in the form of a $580m (£465.3m) acquisition by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, one of the world’s biggest ever media conglomerates. In the same year, Myspace CEO Chris DeWolfe turned down a $75m (£60.1m) offer from Mark Zuckerberg to buy rival Facebook. 2006 saw Myspace sign an advertising deal with Google worth $900m over three years, where they had exclusive rights to provide web search results and sponsored links on the social media platform. “The Myspace deal is looking like it is going very, very well for us,” said then-Google chief executive Eric Schmidt a year into the deal.

The organisational cracks were evident early on. In a 2007 column for The Atlantic, Emmy-award-winning founder of Ish Entertainment Michael Hirschorn, said that Myspace “relies too much on the packaging and marketing of tools that exist elsewhere on the web. They lack a compelling retention mechanism, which leaves them open to the quickly changing loyalties of their (mostly young) users.” When asked by the Wall Street Journal if newspaper readers were drifting off to MySpace, Murdoch muttered, “I wish they were. They’re all going to Facebook at the moment.”

The company had a myopic vision and lacked strategic direction, according to Maria Santacaterina: “Myspace didn’t respond to customer needs or differentiate its products and services from fast-rising competitors, such as Facebook with an 'easy user interface,' which meant the early lead began to fade.” News headlines of a platform infested with sex pests saw parents panic and lose trust in Myspace to keep their children safe, despite removing 90,000 registered sex offenders from the site. The lucrative partnership with Google also became a poisoned chalice for Myspace. A former Myspace executive close to advertising sales said, “We were incentivised to keep page views very high and ended up having too many ads plus too many pages.”

By 2011, and after several board reshuffles and employee cuts, News Corp. had lost patience and put the company up for sale. Following a $156m loss in Q4 of 2010, Myspace had a price tag of $200m (£160.4m) but it was snapped up by online advertising firm Specific Media for a rumoured $35m (£28m). The company still exists today but is a shadow of its former self. Ellie McKay says, “Successive changes in ownership meant the company lost its purpose (original social network, platform for entertainment and music streaming) and fundamentally lost its identity.”

Roundup

“Companies need to constantly adapt and evolve their strategies to stay competitive or else risk becoming stagnant and obsolete as they will be outpaced by their competitors.” - Olga Valadon, management expert

“Often, as a business grows, the entrepreneurial spirit that made it a success in the first place dies along with that growth – as most large businesses are invariably run by accountants. Retaining the ethos that made the business a success in the first place – and seeing the vision early in new and potentially disruptive ideas – is key for any business that wants to prosper in the long term.” - Jonathan De Mello, retail expert and founder of JDM Retail

“Every business says that it is ‘customer-centric’. However, the reality is they rarely are, and they need to be honest with themselves about it. They tend to sit in their own echo chamber conforming to ‘category norms’ and really listen deeply enough to what people really need and feel. They fail to think radically outside of the walls of their category and adapt to fundamental changes in customer behaviour.” - Sam Page, CEO of digital agency 7DOTS

“Business leaders must not only disrupt but be prepared to be disrupted, to embrace change as the only constant, and to understand that the true disruptor is always looking to the horizon, not just to the bottom line. Often exhausting yes, but that’s where the need arises to work smarter and in my opinion that starts with emotional intelligence and taking customer insights and relationships to a new level of expertise." - Kate Hardcastle MBE, a leading consumer engagement specialist

Related and recommended

One leader turned heartbreak into a movement and built a blueprint for purpose-driven growth along the way

A building in Glasgow is testing out a new concept, combining a co-working space with accommodation for hotel guests and a hall of residence for students. Can they all get along?

Personal branding expert Amelia Sordell explains how to make LinkedIn work for your business

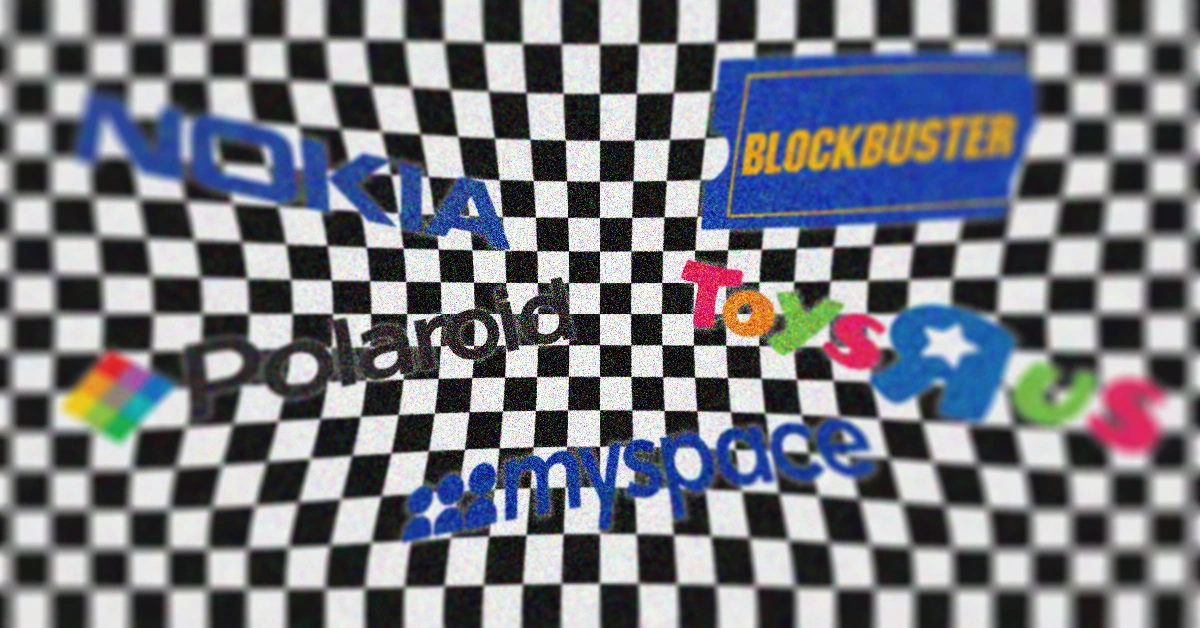

Organisational psychologist John Amaechi challenges leaders to drop the ego, embrace humility and build organisations that thrive