All too many people have not heard of Dame Stephanie Shirley, but they should have done. She launched a business that grew to employ 8,500 people and was sold for £2.3bn. She made more than 70 of her employees millionaires from the sale. She’s given away so much money that she fell off The Sunday Times Rich List. But there is much more to her.

Aged five, Shirley and her nine-year-old sister were sent to the UK on the Kindertransport to escape the Holocaust. Less than two decades later, she launched a business at a time when women weren't allowed to work in the London Stock Exchange, drive a bus or fly a plane. They also needed their husband’s written permission to open a bank account.

Before starting her business, one of her first jobs was at the Post Office research station in Dollis Hill. The renowned north London operation was where Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, was created.

Colossus played a pivotal role in the Second World War, used by the codebreakers at Bletchley Park to decode messages involving German defence tactics. “It was so unreliable,” she recalls, “that we used to measure the average time between faults. But I fell in love with computing.”

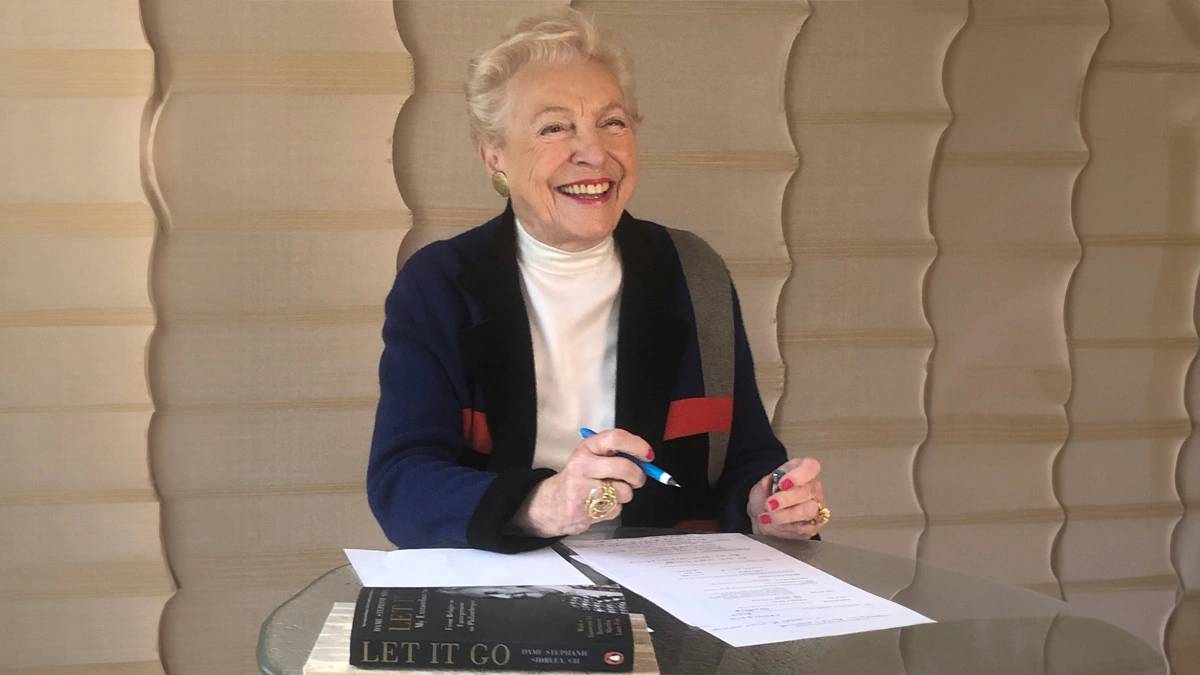

The concept for her company, Freelance Programmers, was born out of frustrations with sexism and inequality in the workplace. “Several of my colleagues, when told of my plan, laughed openly,” she says in her autobiography Let It Go: My Extraordinary Story – From Refugee to Entrepreneur to Philanthropist.

“I presume the rest laughed in private. Not only was the plan mad, but there was also the awkward fact that I was a woman. I was so discontented with the social environment that women had in the 1960s that I set up the company as an exemplar of what women could do.”

It was a novel concept for many reasons. First, it sold software. Not a revolutionary idea through the prism of modern understanding, but customers didn’t buy software in those days. “They expected that to be thrown in for nothing, like a manual for a new car,” she says.

Second, at first it was entirely staffed by women working from home at times that suited them. They used to play tape recordings of office noises in the background of phone calls with clients to mask the fact they were women working at home looking after their children.

That wasn’t the only thing Dame Shirley had to mask. She grew frustrated with the lack of response to letters drumming up business in the early days. That was until her husband Derek pointed out that perhaps the problem lay not with the letters but with the signature at the bottom.

“It was not unreasonable to speculate that many potential customers, seeing the words ‘Stephanie Shirley' at the bottom of a letter, would refuse to take proposals seriously, simply because I was a woman,” she says. “Derek suggested testing this theory by signing a few letters ‘Steve Shirley' instead. I did so, and people began to respond. I have been Steve ever since.”

As the business grew, Shirley’s focus turned to rewarding her freelance programmers. She introduced a profit-sharing scheme in 1966 that would form the basis of a co-ownership scheme that has gone on to define her legacy. But scaling was not without its challenges.

In January 1973 there was a stock market crash. By 1975, UK inflation was touching 25 per cent and the company began to struggle. “In short, I developed a liquidator's mentality, getting rid of almost anything that could be got rid of, until there was scarcely anything left of the company but its name and its core ideas. If we had relied on economic recovery to save us,” she says, “we would have gone out of business.”

Saving the company mattered because she knew it meant more than profit and loss statements. “I think what drove me was that it was a campaign for women,” she says. “I knew that if we failed, not only had I failed but people would say about women in general, ‘we tried that once and it didn't work’.”

The company grew by doing work for the likes of Penguin Books, Esso, Bird’s Eye and the Department of the Environment. One of its most notable jobs was programming the black box flight recorder on Concorde. As the company scaled, she brought in new people to take the business to the next level. She talks about this time in the autobiography: “The harsh truth was that, if I wanted it to stand on its own two feet, without my constant intervention, I needed to stop thinking of it as my company.”

The company continued to morph and evolve under the leadership of others. Its name changed to F International, to F.I. Group and then to Xansa before it was sold in 2007 to the French company now known as Sopra Steria. This time and capital gave Shirley the opportunity to focus on her newly acquired passion: philanthropy.

Her late son Giles was born with severe autism at a time when it was not fully understood. She would be the force behind the charities Prior’s Court School, for young people with complex autism, the residential home for autistic people Kingwood, and Autistica, the national autism research charity.

“I get great pleasure from seeing my money working to such good effort,” she says. “To that extent, good philanthropy is like good business: the reward comes from seeing a system achieve what you wanted it to achieve.”

She’s quick to point out that she believes philanthropy is going to be one of the megatrends of the next 50 years. “Governments everywhere are paring back the welfare state. The societies that do not wither as a result will be those in which philanthropists step forward to contribute as they see fit. If my current work can help persuade those who have something to give that it is worth their while to give it, my ambassadorial efforts will not have been wasted.”

Profits from the sale of her autobiography go towards Autistica. As a read, it’s a wonderful look into the mind of an entrepreneur, at times brutally self-reflective and honest but touching wonderfully on the trials and tribulations of scaling a business. It opens with a moving passage:

“Without my being fully aware of what was going on or why, a large number of good-natured strangers took it upon themselves to save my life. A simple resolution took root deep in my heart: I had to make sure that mine was a life that had been worth saving.

“This is very relevant to my business life because the fact that I was a child refugee means that I have resilience. And people remember entrepreneurs for our successes, but the thing that really distinguishes us is an ability to recover from failures…”

Who can’t relate to that?

Related and recommended

With Labour committed to spending more on defence, we need to be clearer on the trade-offs – while realising ultimately it can boost the economy

Labour believes a trade deal with the US will change its political fortunes, but there are numerous obstacles in the way

The Olympic cycling champion has brought lessons from his time in sport to his work in business

How do you build a company culture that nurtures game-changing ideas? Start with mindset, feedback and failure