From global talent pools to AI-powered documentation, a work-from-anywhere model is a new way of thinking about productivity, innovation and teamwork

Less than 5% of UK CEOs and Founders scale their mid–sized business to greatness.

We exist to change that.

Business Leader is a membership community for ambitious CEOs and Founders of mid–sized companies in the UK. Our mission is to double the number of large businesses in the UK by empowering mid–sized CEOs and Founders to scale effectively, unlocking new growth opportunities and shaping the future of UK business and our economy.

If you're serious about scaling with at least £3 million of annual revenue, this is where you'll push through boundaries and gain access to the tools and support you need to grow faster, scale smarter and win.

Start your journeyYou'll be in good company

Connect with the UK's most ambitious CEOs and Founders from top businesses like these.

How we do it – we meet you where you are

You'll join a stage–based forum of other ambitious CEOs and Founders, led by coaches who've helped scale high–growth businesses. You'll build your personalised path using our proven 9-step Growth Blueprint – supported by world–class content and events that deepen your learning, sharpen your thinking and accelerate real progress.

It's everything you need to scale up and go further with the power of peer–to–peer support and a thriving community around you.

Join a peer group

Connect with similar CEOs and Founders and exchange insights in a trusted, collaborative environment.

Build a growthprint

Unlock potential with your strategic guide to driving innovation and achieving sustainable success.

Get expert coaching

Elevate performance with personalised guidance from industry leaders.

Scale better, faster

Graduate to the next growth stage and find new success for your business.

Experience our world–class content

Big ideas. Bigger impact. All in one place.

Explore the UK's only multimedia hub built for scaling CEOs and Founders – featuring our magazine, summit events, top–ranked podcasts, exclusive interviews and tactical masterclasses across leadership, funding, growth and more. Visit our content hub

Insights from the UK's leading business minds

Stay ahead with the latest strategies, trends and insights from the UK's top CEOs, Founders and business experts. From exclusive interviews to expert analysis, our editorial content brings you the knowledge you need to scale your business with confidence.

Hand–picked for you

A clear and inspiring vision is key to motivating a team, driving growth and turning bold goals into lasting impact

The US is often the first stop for UK businesses looking to expand, but traps lie in wait for even the best prepared. Here are five tips for success

Steve Jobs. Jeff Bezos. Taylor Swift? A new book makes a compelling case for why the world’s biggest pop star belongs in the pantheon of business masterminds

By focusing on underserved markets and ethical supply chains, S’Able Labs is hoping to position itself for long-term success in the competitive beauty industry

The sale of cricket franchises for nearly £1bn shows the power of a good story over data when it comes to selling a business to investors

How to swap time-wasting activities like doom-scrolling on your phone for new goals at home or work

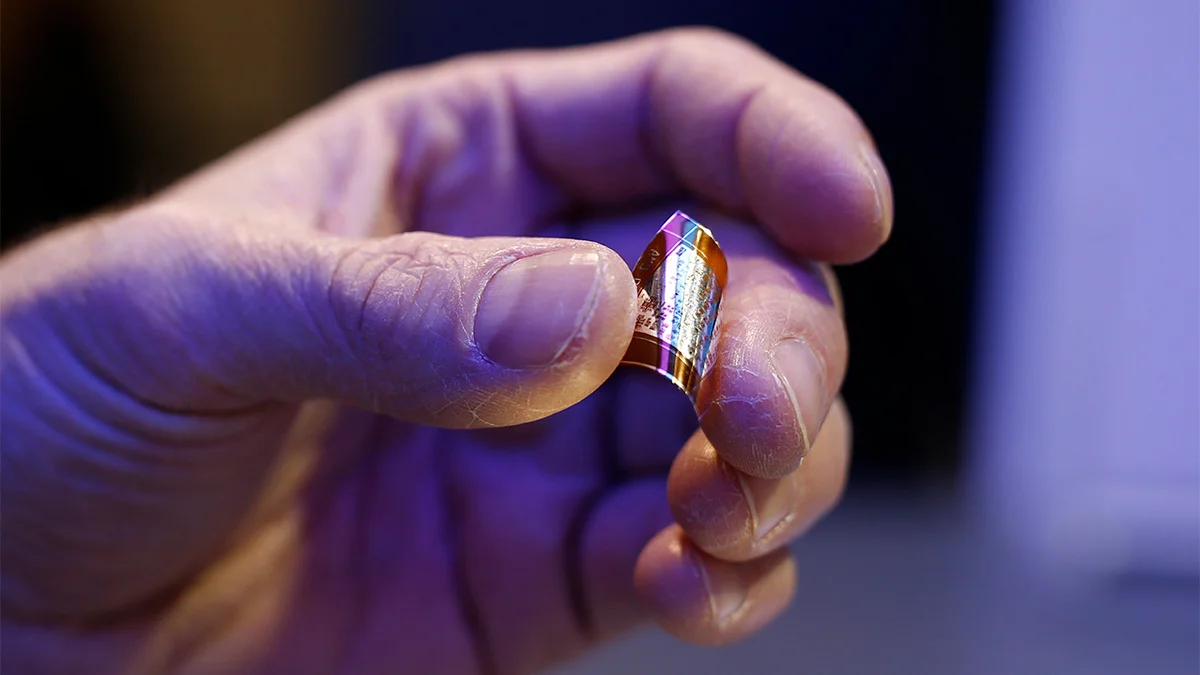

A new generation of engineering companies is emerging in Manchester thanks to the extraordinary strength and elasticity of graphene

Trusted by ambitious business leaders

Julia Langkraehr

Expert EOS ImplementerAndrew Moses

Managing Director, The Config TeamRichard North

President, WoW! Stuff

Ready to accelerate?

If you're serious about scaling your business, you need to be here.

Start your journey