Ikea’s boss: We’ve never made so many mistakes

Ingka Group's CEO Jesper Brodin has had to return Ikea to its entrepreneurial roots to transform the retailer for the digital age

Read or listen to our interview with Peter Jelkeby, the CEO of Ikea’s United Kingdom and Ireland business, here.

For my appointment with Ikea boss Jesper Brodin, I line up with hard-hatted construction workers at the rear of an old stone building near Oxford Circus in central London. The property has been completely gutted and then renovated to become the latest inner-city Ikea, which is due to open in spring 2025. This particular superstore has been built on a new model for the Swedish company.

The store will be “the crown jewel in our basket of city stores”, says Brodin when I find him in a suite of temporary offices. The company now has 26 of these smaller, inner-city outlets, designed for digital-savvy shoppers who perhaps don’t have a car. It’s part of a new omnichannel approach, offering smaller household products and digital design services. Customers can collect items bought online or organise for them to be delivered.

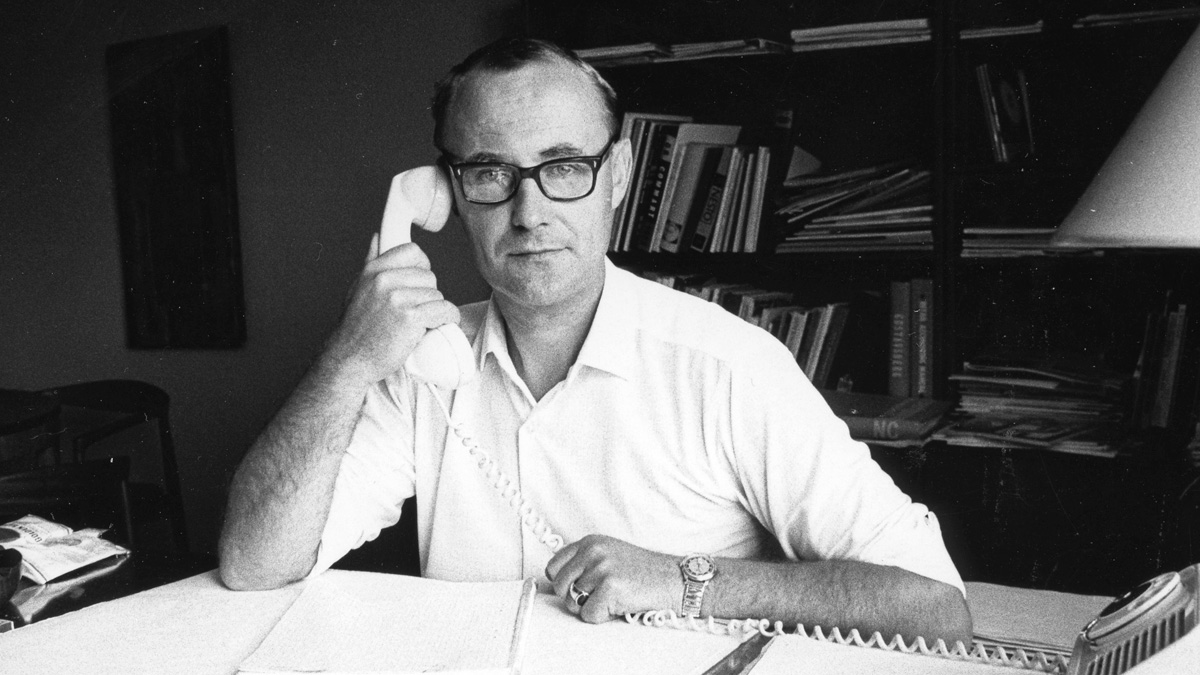

For a company steeped in its own history, Ikea is now ready to do things differently. Yet Brodin, who is leading the charge, retains a strong personal connection to its traditions. Shortly after he joined the company from the University of Gothenburg in 1995, he worked as an assistant to the founder Ingvar Kamprad. Brodin began working for the firm in Pakistan purchasing textiles, then moved on to another role in south-east Asia. He was recruited to be Kamprad’s assistant in the late 1990s, having been identified as a rising talent within the company.

“Ingvar told me that the assistant’s job,” recalls Brodin, “is everything between writing the minutes and leading the company.” It was seen as a platform for younger staff to get a broader view of Ikea and learn its DNA. It was also a chance to build a relationship with the charismatic founder and absorb his sense of mission.

For Brodin, it was “back to school” when working alongside Kamprad: “He taught me a sense of loyalty and responsibility [towards the company]. Ikea is deeply purposeful, we work for the betterment of the world, particularly for ordinary people with thin wallets.”

When Brodin became chief executive of Ikea’s holding company Ingka Group in 2017, Kamprad was still alive and Brodin benefitted from his boss’s advice. Kamprad was a born entrepreneur who founded Ikea in the 1940s, aged only 17, as a catalogue-based, mail-order business selling furniture. Its name comes from his initials (IK), the farm where he grew up in an impoverished childhood (Elmtaryd) and the parish where it was located (Agunnaryd).

One of his first great innovations, in the 1950s, was to create a showroom so people could see furniture before they bought it (it also served food, so customers would not leave for lunch or dinner). Kamprad had to make the only capital raise in the business’s history, a SEK500 (£36 in today’s money) bank loan.

In the decade that followed, the company would develop its next selling point: in-house designed, flat-packed furniture, which was easy for customers to transport and assemble at home. As Kamprad wrote in The Testament of a Furniture Dealer handbook for the business in 1976, Ikea’s mission was and is to create “a better everyday life for the many people”, with well-designed, low-priced products.

Now more than 80 years old, Ingka Group recently reported annual revenues of €41.8bn (£35bn), with 860 million shoppers at 574 stores worldwide. It employs 162,000 people and operates in 31 markets globally, with nearly three-quarters of sales occurring in Europe.

Why Ikea had to evolve

However, the look and layout of its famously open-plan retail spaces are changing. Ikea’s blueprint for global expansion began with its second store in 1965, on the outskirts of Stockholm with a huge car park, where customers collected their own flat-pack furniture from the warehouse shelves. This template led to it becoming the world’s largest furniture retailer. But in 2014 it opened its first smaller, inner-city store in Hamburg, signalling a new approach that Brodin has continued.

Growth had stalled for several years from 2007 as it sought a response to the rise of e-commerce, but digital channels now make up slightly more than a quarter of its business. Brodin has overseen the roll-out of Ikea city stores in Paris, Shanghai and Vienna already.

It can be notoriously difficult for CEOs to take a company in a new direction when the original founder is still active in the business. Brodin had to persuade Kamprad that embracing a digital, omnichannel approach and investing in inner-city stores was a good idea. The founder was known for not being greatly interested in digital developments.

Brodin recalls a telling moment as Kamprad’s assistant: “He asked me what I thought of IT and computers. [I realised] the scepticism at his end came from a fear of cost. I asked him if he had a computer, and he said ‘no’, so I offered to buy him one.”

After a couple of hours together on the web, Kamprad partly changed his mind, says Brodin, though he was mainly excited by the cost-saving opportunities. “But until his last days, he was always a bit sceptical.” Kamprad died in 2018, aged 91.

Yet change was essential. Ikea had become a victim of its own success in the early 2000s, Brodin says, because its store-based model was working so well. The leadership didn’t recognise the digital revolution that was endangering its business model.

“We were a bit behind in exploring the opportunities,” says Brodin. “By 2015 we could see customers were shifting to competitors due to the basic reason of convenience, so our digital revolution started with listening to customers and their needs.”

One power Ikea has never lost, as Brodin knows well from his time on the supply side of the business, is the ability to integrate vertically and keep down costs for consumers. Since the 1970s, Ikea has invested in owning the value chain where possible and has gone as far as to buy its own forests so it can produce and cultivate wood.

The company owns nearly 15 per cent of the manufacturing processes for its products, cutting down on waste. This is why it can produce best-selling items, such as its Lack coffee tables, for what Kamprad called “a breath-taking price”.

Ikea’s cash position also gives the company a lot of clout. Since it is not paying dividends to shareholders, it can continually reinvest in the business. Not only does it own all its buildings rather than rent them, but it often buys up surrounding real estate too, a strategy that began with its expansion into Russia in the 2000s.

Ikea’s leadership team realised the halo effect any new store created in a neighbourhood, each one becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy of urban regeneration. This investment principle extends to their latest phase of growth in city centres. Ikea often owns many of the malls in which the new stores operate.

Not being a public company helps a lot, says Brodin. “You could argue it adds a healthy pressure on performance, but it also brings a risk of being too short term,” he adds. “All CEOs know that sometimes you need to make decisions and provide structures that will make the company thrive across a three-, five- or seven-year perspective.”

Ikea’s entrepreneurial journey

Ikea’s approach to scaling globally is the very opposite of a modern phenomenon such as WeWork (to cite a cautionary example), which scaled rapidly thanks to venture capital. Ikea’s international expansion since the 1970s has been entirely organic, and as slow and ponderous as its legendary in-store experience.

Its corporate structure and cash position meant it could be independent-minded and deliberate in its actions. It is also in the strange position, for a company of its size, of not really having a comparable direct competitor to keep it sharp. No other global retailer makes and sells its own furniture designs.

Brodin recognises the company needs to become more agile and responsive. That’s the lesson of its slow response to the much-needed digital consumer update. “In Ikea, we need to become better at making fast decisions and act on experimentation even faster. Sometimes our structure can make us a little bit too long-term,” he says.

The roll-out of inner-city stores has put Ikea on a slightly unfamiliar footing, he admits, challenging its own culture. “We’ve been on an entrepreneurial journey for the past seven years,” he says, “in an area where we’ve tried and tested more than we’ve done in a very long time. We’ve never made so many mistakes.”

They are slowly finding out what inner-city customers want, one store at a time. And it turns out that they still want some of that labyrinth-style, shopping-as-journey experience – rounded off by a portion of meatballs.

“I remember one of the last times I met Ingvar,” says Brodin, “I asked him about the future of Ikea and how we should think about it, and he said, ‘You should think long term’. I asked him how long term, and he said ‘200 years!’”

So what would Ingvar Kamprad make of this new-style Ikea store on Oxford Street? Brodin smiles. “I can promise you two things, he would be massively impressed and recognise himself – and at the same time he would give me a long list of things I need to do much better.”