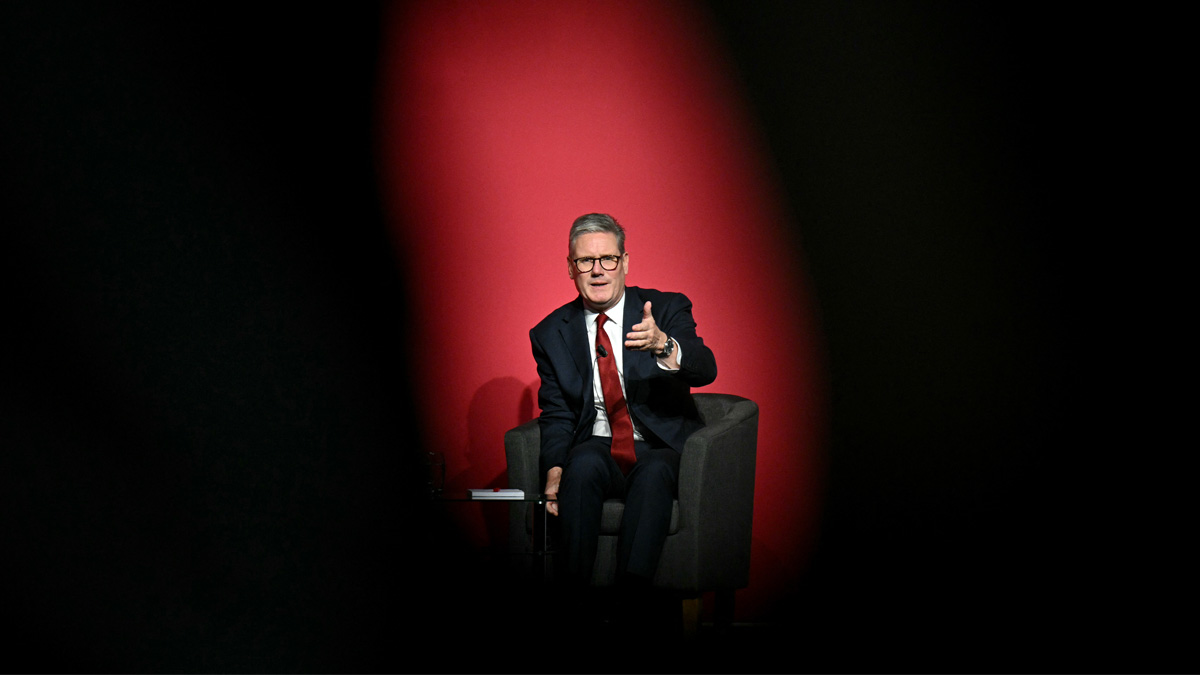

Labour’s problems are not a failure of storytelling but of leadership

Sir Keir Starmer and his party achieved power by avoiding saying too much but without a compelling narrative, they can’t expect to stay in government for long

(Image: Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images)

(Image: Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images)

It’s just an anecdote, but a strange thing happened to me on general election night this summer. I felt nothing, nothing at all – the first time that had happened across the seven elections since I’ve been old enough to vote.

If we discard thoughts and attend to feelings, blankness was the thing that registered with me. Not a weakly optimistic: “Good, they’re gone.” Not a knowing: “But this lot will get found out soon enough.” Not even: “A plague on both your houses.” Nothing. An empty page.

As though what was happening – had happened – belonged to a parallel universe in which people pretend to care about a circus that is gradually becoming detached from reality. Which is why I also felt a second instinct: I anticipated boredom at the inevitable political analysis decoding what it all meant, because it didn’t feel like it mattered much.

Experience in other spheres tells me that when people emphatically choose something they don’t know and (worse) can’t be bothered to find out about – as seemed to be the case with the electorate and Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour – then the underlying psychology contains a dangerous mix of complacency and resignation. With no real solutions on offer, why bother to interrogate the superficial ones on the table?

It doesn’t matter. Which of course matters all too much. And as late evening on election night tipped into early morning, I realised how much I feared and disliked my own cynicism. Now, five months on, the void is playing out politically. Beset by one problem after another – gaffes, freebies, brawls – Labour has failed to inspire the feeling that the country is being significantly refashioned or led.

After its limp party conference, Labour’s grandee spin doctors debated why everything was so flat. Of course, there’s always the right-wing press to blame, but favourable insiders speculated that Labour ought to be focusing more on having a convincing narrative to drown out the noise. If only Starmer could summon up a better story to tell, the logic went, then all the annoying negative little stories would go away.

The counterargument seemed too heretical to raise: the absence of a compelling narrative wasn’t a failure of storytelling, it was a failure of leadership. Rustling around for an over-arching story amid a series of gaffes pins a lot of hope on tactical ingenuity.

If a prospective prime minister can get through an entire election campaign without impressing on voters his vision for the country – beyond not being a Tory – why would he stumble on one a few months into office, just when chaotic reality is kicking in? In his private, innermost thoughts, I wonder how Starmer now feels about the electoral campaign that ended in his landslide victory. Job done or a missed opportunity? (I hope the latter but fear it is the former.)

As political messaging has become more sophisticated and targeted – tickling one susceptibility after another – so too has underlying scepticism about political messaging among its target audience. Professionalisation of communication makes pros of the listeners, too. Paradoxically, we end up listening out for exactly the things that the PR experts train communicators to avoid: accepting personal risk and acknowledging underlying truths. A useful narrative is identifying the big things you are going to be judged on and explaining how you are going to address them.

A leader’s first impressions are hard to shift. I was initially tempted to use the mini-scandal around Starmer’s freebie clothing as a mischievous introduction to this column. How can you spend £32,000 of someone else’s money and still look no better dressed? Because however expensive the luxuriant fabric or skilled the craftsman’s handiwork, luxe tailoring still eventually comes up against the gravitational facts of the area it’s being stretched across. And wool and thread can only do so much heavy lifting.

Having thought better of the introduction, I then realised that the metaphor, though superficially catty, offers a more sympathetic analogy about the difficulties facing any government, given the internal contradictions of the electorate about what the state should do. We keep thinking a better suit is the answer to the country’s problems, but it never is. Because it’s pulling at the stitching and stretching the weave, and everything is coming apart at the seams. And deep down, though we carry on shopping in privileged and idle distractedness, we know it’s not really the suit that’s the problem – it’s the body.

How much longer until we are ready to hear the truth? Too many expectations are being wedged into too small a budget. And it’s time to get in shape. Swallowing the latest sales jargon – from Boris Johnson’s “cakeism” to Starmer’s “fixing the foundations” – extends the fantasy that a couple of darts in the back seam or letting out the waist by a notch or two will transform the overall effect. But the underlying body politic, of course, is just the same. So, buyer’s remorse kicks in and the electorate gets disappointed and cross with the salesman who artfully pandered to our knowing self-delusion.

In one respect Rachel Reeves’ Budget, though less calamitous, shares a quality with Kwasi Kwarteng’s. One offered more taxes without consequences. The other promised less taxes without consequences. More than the tilt of the particular ideology, more problematic is the unified shying away from those consequences.

Starmer achieved power by avoiding saying things. His pitch was: “Britain’s not working” – followed by silence. Into the void comes the inevitable second question: how are you going to fix it? If he doesn’t dare to spell it out soon, we can only guess he has calculated it will be someone else’s problem soon enough.

Ed Smith is director of the Institute of Sports Humanities and the author of Making Decisions