Great success can come from sharpening your focus

Ed Smith explores the journey of England bowler James Anderson and why it holds lessons for business leaders on career development

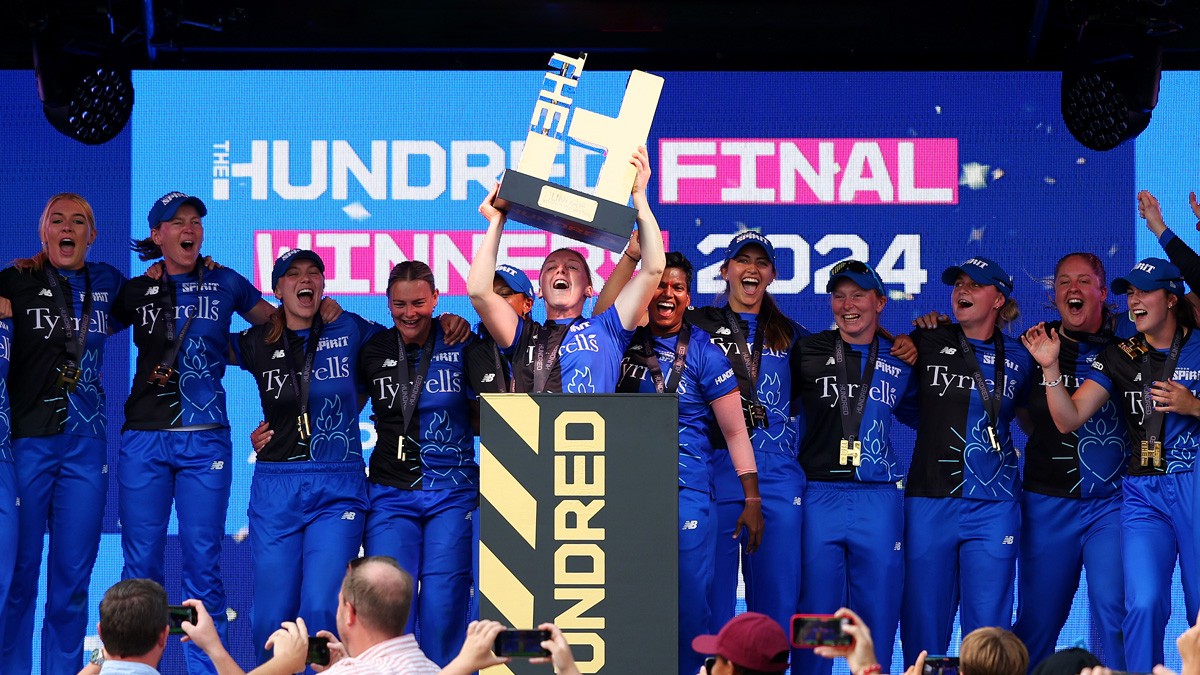

(Image: Gareth Copley/Getty Images)

(Image: Gareth Copley/Getty Images)

Many of us form our worldviews around our own capabilities, ever vigilant for patterns of success that validate personal decisions. “He posits a principle,” in Nietzsche’s unimprovable barb about Wagner, “where he lacks a capacity”. I remember hearing a professional coach explain why he had signed a new player: “He was the closest thing I could find to me.” All too understandable; but the coach didn’t last long.

The opposite way is more useful: learning from people who find great success at the other end of the career spectrum. So those of us who have sometimes argued in favour of breadth and “portfolio careers” should take extra care to study the shape and trajectory of James Anderson’s remarkable achievements as an England cricketer.

Anderson retired this summer with more Test match wickets (704) than any fast bowler in history. He made his debut at 19 and retired at 41. No second strings required, and not many off-days either. Just persistent, record-breaking excellence for 188 Test matches. There were several layers to Anderson’s specialisation. First and most obvious, as the opening bowler and number 11 batter, no one bowled ahead of him or batted below him.

Nothing grey or confusing about those facts. And they suited Anderson’s understated perception of how things ought to be: clarity, accountability, responsibility. If you compiled a showreel of all the numerous times he bowled the first ball of an innings, you would see how rarely he missed his spot. A job to do, a tone to set — the band’s metronome. His former captain Alastair Cook always said that Anderson’s ability to begin each new innings with an accurate, perfect-length ball would only be appreciated after he had gone. Making precision look easy is a classic trick achieved by the greats. A second layer emerged in terms of formats. Of cricket’s three main formats (Tests, one-day internationals and Twenty20), though proficient at them all, Anderson played exclusively in Tests for the final nine years of his career.

As his focus narrowed in terms of formats, his returns improved still further: his career during his years as a “Tests-only” bowler reads 324 wickets at an average of 22.62 (which is almost off the spectrum). The third aspect of Anderson’s mastery was the evolution of his archetype. Anderson’s hyper-consistency in terms of output was powered by his stranglehold on accuracy.

One of the most interesting data projects I have experienced in sport was England cricket’s deep dive into understanding the archetypes of bowlers who make a real success of Test cricket. Imagine four different continuums: speed, accuracy, movement and bounce. Now imagine all international bowlers are plotted along each of the four lines. We learnt that bowlers ranked in the world’s top 10 truly excelled in two or three categories. One on its own was rarely enough.

This has repercussions in terms of trade-offs. For example, it’s a common oversimplification to say that speed is a prerequisite at an elite level. Yes, gaining speed might help a bowler become more likely to succeed in Tests. But if extra speed is achieved at the expense of, say, both movement and control, then the bowler could end up below the line in two categories – and hence less likely to achieve a sustainable “Test match archetype”.

In Anderson’s case, the final shape of his career looks very different from its early direction. As a young prodigy, Anderson was known as a wicket-taker, but at the expense of keeping the runs down. That changed over time. He sustained the ability to create movement in the air and off the pitch, but he added the art of grinding down opponents through relentless accuracy and starving them of scoring opportunities.

Anderson added a dimension, but without compromising elsewhere. He became a patient torturer, always playing the long game, within the individual match and the arc of his own career. Just like a business has to grow into its brand, every great athlete evolves into a performance DNA that ends up looking natural (and inevitable) once achieved. Through a mixture of trial and error and self-awareness, they become themselves.

I saw Anderson up close near the very beginning and then near the end of his extraordinary journey. After a decade mostly away from cricket doing other things, I came back into the game aged 40 as an England selector. By chance, before the first match back at the sharp end in 2018, I found myself having lunch with Anderson in the pavilion at Lord’s Cricket Ground. He relayed a conversation he had just had with his friend and colleague Stuart Broad. Broad had asked Anderson if he had encountered me before; Anderson replied that we’d played three Test matches together in 2003.

It was a time so distant that the year was almost out of sight from the perspective of cricket in 2018 — even for a knowledgeable elder statesman such as Broad. From my perspective, 2003 did seem like a lifetime ago — certainly two or three careers ago. But Anderson still had another six years (and 173 wickets) to go at the top of the same mountain.

Because success flows from the perpetual and chaotic interplay of talent, effort, resilience and chance, the hardest thing is assessing where we stand within the body of our own work. About to break through? Already plateauing? Or worse than that?

Some people tilt towards finding their purple patch and sticking it out. Others can tire of the last thing and switch focus. It’s worth remembering that both intense specialisation and curious restlessness bring their own risks. I suspect most people move up and down the continuum, figuring it out as they go.

Only the very few, like James Anderson, find that one style offers the perfect solution.

Ed Smith is director of the Institute of Sports Humanities and the author of Making Decisions