Exploring the South West’s hidden potential

Businesses are breaking new ground across the region but do they need to shout louder to get vital funding?

Some 20 minutes’ drive northwest of Bristol, Isambard-AI, one of the world’s fastest supercomputers is now online in its temporary home at the National Composites Centre. Thanks to a £225m government investment, Isambard-AI will be ready to drive a range of scientific breakthroughs.

At its offices in Exeter and Newquay in Cornwall, Intelligent AI, a start-up that helps the insurance industry to recognise risks around commercial and residential property has just received £1m in funding to scale up the business nationally and into the US. Two stories at different ends of an industrial revolution, both sparked by AI: a giant government-backed project and a commercial start-up.

Both at different ends of a region, the South West, which feels left behind when it sees the clout of its regional rivals, the Northern Powerhouse and the Midlands Engine. Yet the South West is an anomaly. It can be hard to detect any thread between the Isles of Scilly and Swindon, or a sense of regional identity.

Historically, the region that includes Bristol, Exeter, Plymouth and Bournemouth has been lumped together following the creation in 1999 of the now-defunct South West England Regional Development Agency. But what comprises the South West now, and should it include the West of England, that is Bristol and Bath and their environs?

Northern Powerhouse and Midlands Engine are unified by their big cities and industrial muscle. On the peninsula, the focus is on blue and green (marine and ecological), while in Bristol it is advanced manufacturing, professional services, deep tech and creative industries. “It’s definitely not one economic geography,” says Paul Swinney, director of policy and research at the Centre for Cities think-tank. “You could make an argument probably for at least four, if not more.”

Stuart Brocklehurst, deputy vice-chancellor for business engagement and innovation at the University of Exeter, doesn’t see it as a competition with other regions. “The Northern Powerhouse contains Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, Hull, Newcastle, and York. It’s not comparing like with like,” says Brocklehurst, who sits on the board of Great South West, a public-private sector partnership for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, Devon, Dorset and Somerset.

He sees the geography as split in two: broadly, the peninsula and the West of England, which has a combined authority and its own mayor.

“They are quite distinct,” Brocklehurst says. “If I go down the hill to the train station from the university, I can be in London almost as fast as I can be in Bristol. The peninsula naturally looks more to London because you can be there pretty much as quickly. Bristol is obviously a major city, the peninsula is overwhelmingly rural and has challenges around the periphery.”

Travel and the low density of the population are hurdles to education and training. But Brocklehurst has plenty to boast about. “Exeter is home to more climate scientists than any other city in the world. Beijing is the second,” he says. “You’ve got the Met Office and the university. The university has more of the top 100-ranked climate scientists than anywhere in the world.”

Further west, Brocklehurst points to Smart Sound Plymouth, the testing ground for marine products and services, and the Plymouth Marine Laboratory leading research into a sustainable ocean. “You have an incredible set of assets around things which are going to be defining a lot of the future world,” Brocklehurst says.

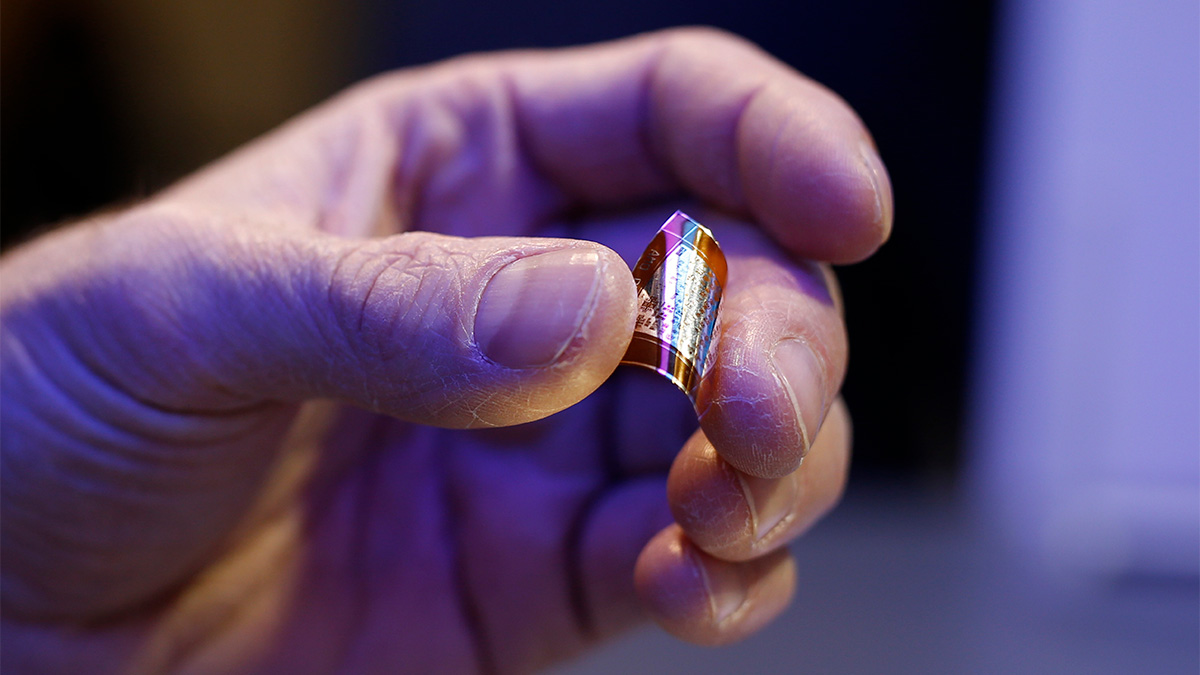

The potential is not limited to the sea. You can discover the county’s tin mining heritage at Helston’s Poldark Mine. The country’s only school of mines is based in Camborne. Meanwhile, Cornish Lithium is working to build a domestic supply of lithium and other battery metals, which are vital for the decarbonisation of the automotive industry.

At Plymouth Science Park, clean tech start-up Altilium is working on recycling old EV batteries instead of sending them to landfill in China. Its first recycling plant, on Teesside, was announced in February.

Tourists may bring in almost £2.5bn a year for Cornwall but Brocklehurst says: “We need to get past the bucket and spade image to see that there’s really important work being done here. Difficulties in communications? Yes, particularly as you head further west. I can be on the motorway in 10 minutes. Obviously, the motorway stops at Exeter. From Plymouth, the largest city in the UK without a motorway, and more so in Cornwall, you have the challenge that everything slows down, by road and rail.”

Dan Pritchard, co-founder of Tech South West, a partnership of tech clusters running from the Scillies to Bristol, understands the drawbacks but sees an upside. “It does make it hard when you’re trying to engage with government, regional government, local government,” Pritchard admits. “But we find it quite an advantage as a business sector representative, as an ecosystem player and as a cluster group.”

For instance, Microsoft is a business partner of Tech South West, but the tech giant doesn’t have time for lots of local engagement. “Coming in at a regional level,” says Pritchard, “you can start to have conversations about innovation or productivity and what the opportunity is.”

Others don’t see it that way. “You’ve got this dilemma,” says Nick Sturge, an entrepreneur who put Bristol’s Engine Shed innovation hub on the map, and now chairs Techspark, a local not-for-profit network.

“Some people say you’ve got to look east to London from the West of England – and not look south or west,” he says. “I don’t think that’s the right answer. No one has really cracked the problem, but the industrial base across the Western Gateway – i.e., looking west – has far more legs to it as a powerhouse concept than the South West – looking south.”

Sturge sees the Western Gateway, a partnership of local authorities from South Wales and the West of England, as a more effective grouping.

“The South West as a whole is completely incoherent,” says Sturge. “Cornwall is a great place, there are some great pockets of entrepreneurial activity, but what is the contribution to the UK? Western Gateway, by working together, can contribute more to the UK than the greater South West. Bristol and Bath collaborating with Cardiff and Cheltenham can do a lot for the UK as a science superpower. The risk with the whole South West is that the whole is less than the sum of its parts.”

But he does remain cautious about the possibilities. “Western Gateway hasn’t fulfilled its full potential yet,” Sturge says. “That doesn’t mean it can’t.” Sturge attributes current successes – of the kind that have led Bristol to be branded as Silicon Gorge – to the legacy of pathfinders such as Inmos, a chipmaker based in Bristol and Newport which was seeded by the Callaghan government and offloaded by Margaret Thatcher.

“The legacy of Inmos is that it bred an entrepreneurial culture,” says Sturge. “It celebrated people leaving to start up their own businesses or setting up the UK offices of a foreign tech company.”

Richard Bonner, who chairs the West of England Local Enterprise Partnership, sits on the Western Gateway board. He sees it as joining the dots. “We’ve got cybersecurity that comes down into Bristol and through the University of Bristol, linked up to Cheltenham and the Golden Valley development, and across into South Wales.”

He adds: “One of the threats we will continue to see is how we bring funding for start-ups coming out of our universities.” He cites Northern Gritstone, which backs spinouts from Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield. “That’s the sort of thing we need to start to develop for ourselves in the rest of England or in the wider region,” he says. “We don’t have a venture capital institution.”

Stuart Harrison, director of FinTech West, which covers the whole South West, says: “The number one challenge is access to funding.” So does the region need an investment vehicle supporting spinouts? “It would certainly help,” says Harrison.

The real battle is to be heard in Whitehall and Westminster. As Stuart Brocklehurst says, “We are constantly having to shout and to make sure that there is awareness of what we’re doing and of the role we play.” They also have to hope that the government is listening.