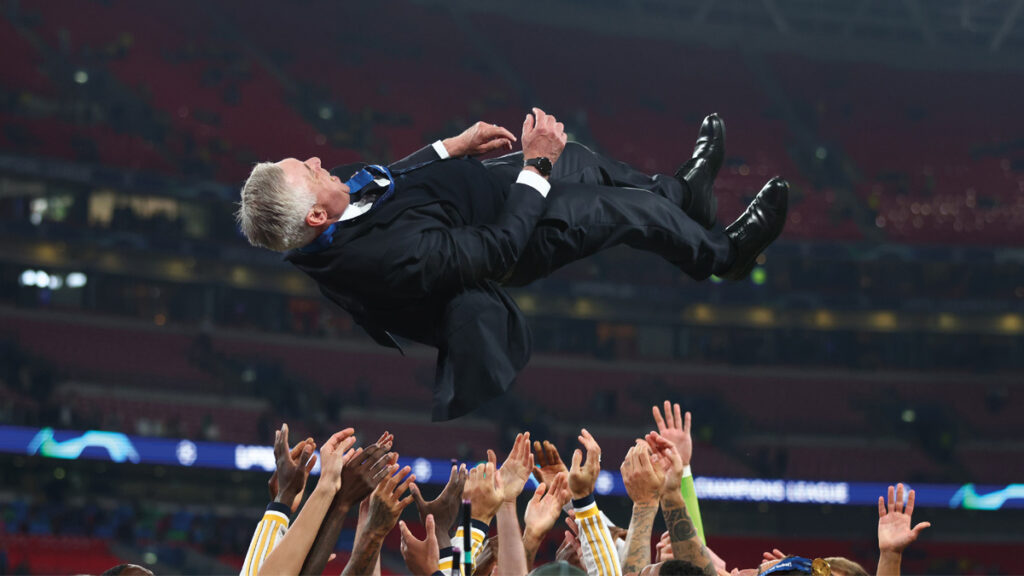

Adaptability over ideology: How Carlo Ancelotti has redefined leadership

In an era where philosophical fervour in sports rivals that of political debate, football managers like Pep Guardiola and Carlo Ancelotti exemplify differing approaches to the game

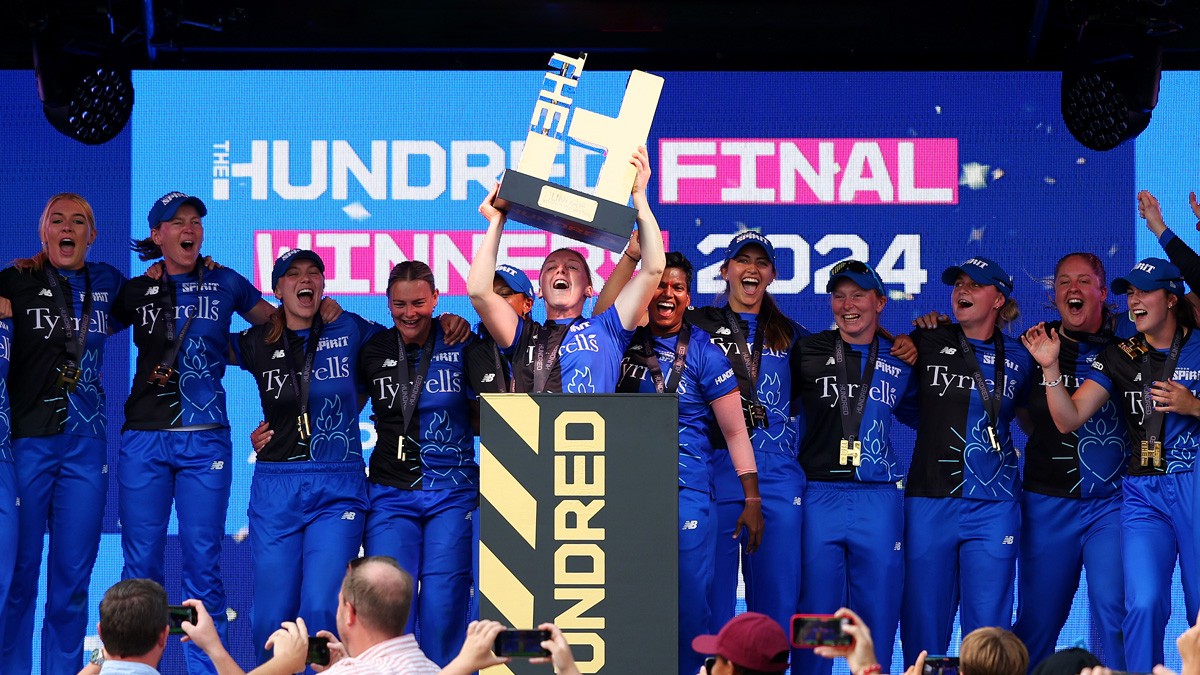

(Image: David Ramos/Getty Images)

(Image: David Ramos/Getty Images)

We are all supposed to be pragmatists now, except in sport. There is an old joke that the US lived out its socialism through American sports (where redistribution and competitive equipoise are common principles) rather than American society.

With similar transference, we now delegate philosophical fervour (absent from political debate) to football managers, especially Pep Guardiola, whose faith in tactical principles – in particular possession and technicality – has swept his sport. Everyone is now encouraged to think like Guardiola, only without his huge intellect or access to oil money. ‘Style of play’ is no longer seen as a privilege but a prerequisite. What’s yours?

Just winning, answers Carlo Ancelotti, with respectful mischief. Somewhat strangely Ancelotti is rarely held up as a managerial type, despite being Guardiola’s main rival as the world’s best football manager. Which is just as Ancelotti likes it: hard to place but with both hands on the cup.

It’s tempting to shoehorn sporting rivalries into clear ideological divides. With Guardiola and José Mourinho, the idealist was defined against the Machiavellian. When Guardiola came under pressure from Liverpool’s former manager Jurgen Klopp, it was framed as the purist against the communicator.

But there is a different kind of argument, one that ranks these clashes of styles, and that is when one side declines to pick a style. You wish to be defined by philosophy and an ideology – I do not. Not much of a headline, but quite a track record: Ancelotti has five Champions League trophies just as a manager. He has two more as a player.

It is often said of Ancelotti’s teams that they are all different. His AC Milan side didn’t play like his Chelsea side, which didn’t play like his Real Madrid iteration, except for the fact they all won. There is no single Ancelotti system, but there is an Ancelotti way. That is a quietly brave kind of decision: many follow a style, only a few trust in following a disposition.

First, Ancelotti believes that football is played by human beings, not cogs in a machine or data points on a graph. And human beings require an emotional connection with their work, you can’t stay good at something without it. “It is my responsibility to help the players stay in love [with football],” he wrote in the preface of his autobiography Quiet Leadership. “If I can do this, then I am happy.” Ancelotti’s teams may not have rigid tactics, but they do have a temperament derived from his humane interpretation of professionalism.

Second, Ancelotti believes in pleasure. Famously devoted to food, he thinks life should be enjoyed. He encourages his clubs to follow the model he experienced at AC Milan, where the training ground has its own restaurant. “Not a buffet,” he has noted wryly, “but a proper restaurant with a waiter who comes to speak with you as a friend.” In sharing meals, teams develop trust and intimacy. Eating is a necessity, but also – when done right – it is a pleasure and a way to build relationships without trying.

The metaphor of a team as a family is often overstretched (teams cannot wish away a necessarily ruthless edge). A family that doesn’t share meals risks becoming an association of cohabiting natives sheltering under the same roof. The same applies to teams. Encouraging and convening around communal experiences is not a team bonding cliché but is fundamental to making groups of people more effective.

Above all, Ancelotti believes in adaptability. He learnt this the hard way, with a mistake he quickly regretted. As manager of Parma, he was offered Roberto Baggio, the definitive Italian playmaker. But at that stage of his career, Ancelotti favoured playing 4-4-2 with two strikers and Baggio didn’t fit that system because he wanted to play behind the striker. “I should have worked with Baggio and found a way,” Ancelotti reflected. When he faced a similar challenge as manager of Zinedine Zidane, he changed the system to fit the player. It has become his trademark skill.

Leading without a policy asks for more of a rival toolkit: sound judgment. Alexander Chancellor, the former editor of The Spectator magazine, said he used to dread being asked to define his editorial policy, to lay out his vision for the magazine. Despite deep confidence in his own judgment, it wasn’t easy to formalise what he was looking for. If pushed, Chancellor would reply: “Well, we should publish some good articles, I suppose.” (Chancellor’s advice comes close to summarising my approach to selecting England cricket teams.) In essence, the editor was looking for good work and he was open-minded about what kind of good it was. And beyond that… well, was there anything?

Chancellor’s position is both braver and more difficult than it sounds. Effectiveness without a strategic wrapper is disarmingly rare. What’s usually termed strategy – mission statements, over-engineered theory, glossy documents laden with abstract nouns – has been misused and expanded to the point where it is now often devoid of content. Strategy is more often a crutch and a diversion tactic, rather than anything usefully strategic.

It’s no coincidence that sport’s growing obsession with a particular style of play has coincided with another term that is used increasingly often and badly: methodology. It’s as though all activities must now pretend to be academic.

Must we really start with some kind of methodology, especially when operating in the humanities rather than the hard sciences? Perhaps not. The iconoclastic Austrian philosopher of science and author of Against Method, Paul Feyerabend, once made the counterargument: “The only principle that does not inhibit progress is: anything goes.”

Ancelotti would probably shrug at the arch tone. But the evidence suggests he understands the point better than anyone.

Ed Smith is director of the Institute of Sports Humanities and the author of Making Decisions